Project Description

What

Printing R-Evolution 1450-1500. Fifty Years that Changed Europe

What

There are authors we never heard of, works we never read… Early printed books covered any subject, not just religious and classical books, but also a substantial amount of current affairs for the needs of everyday life, today almost completely lost. What will survive of today’s digital production?

What was printed in the 15th century?

28,000 editions survive today in 500,000 copies, in 4,000 public libraries and in ? private collections. We know what they are and where they are. The Incunabula Short Title Catalogue (ISTC) of the British Library and the Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke (GW) of Berlin Staatsbibliothek hold this information. Here is a summary:

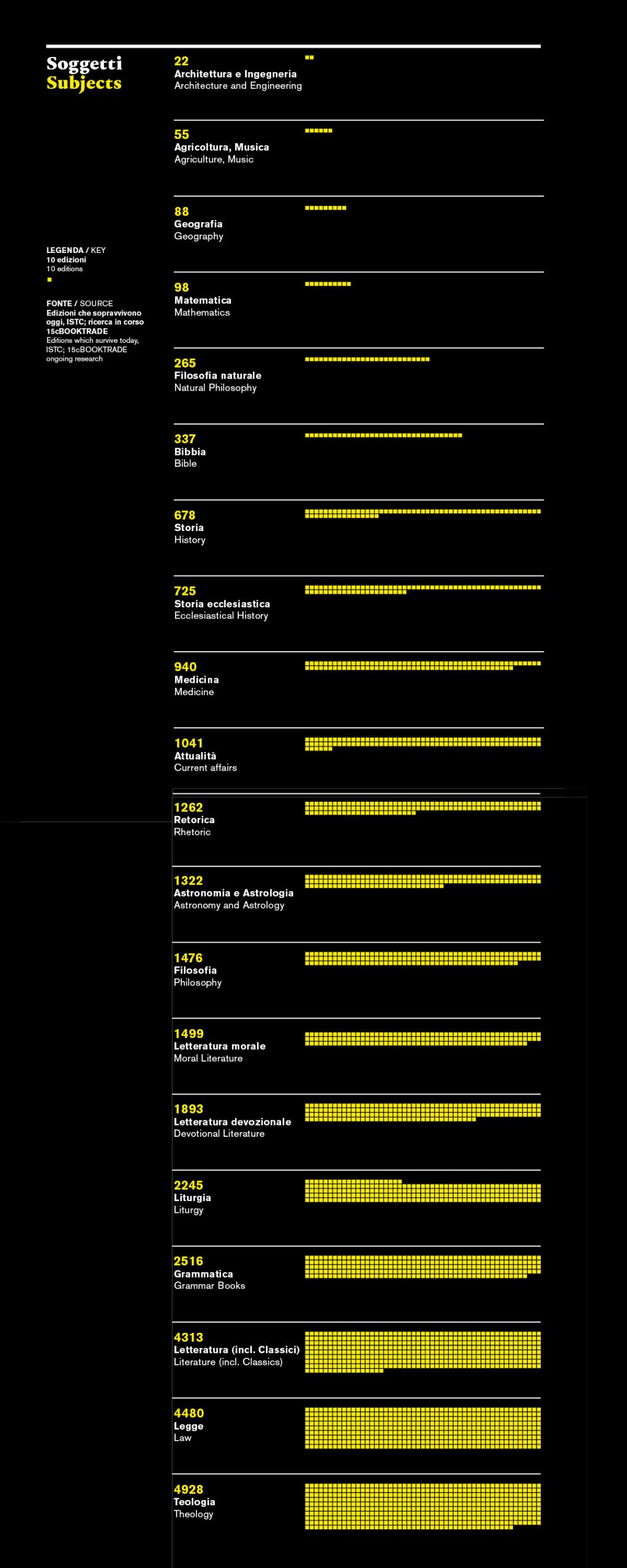

Subjects

A selection of books by subject

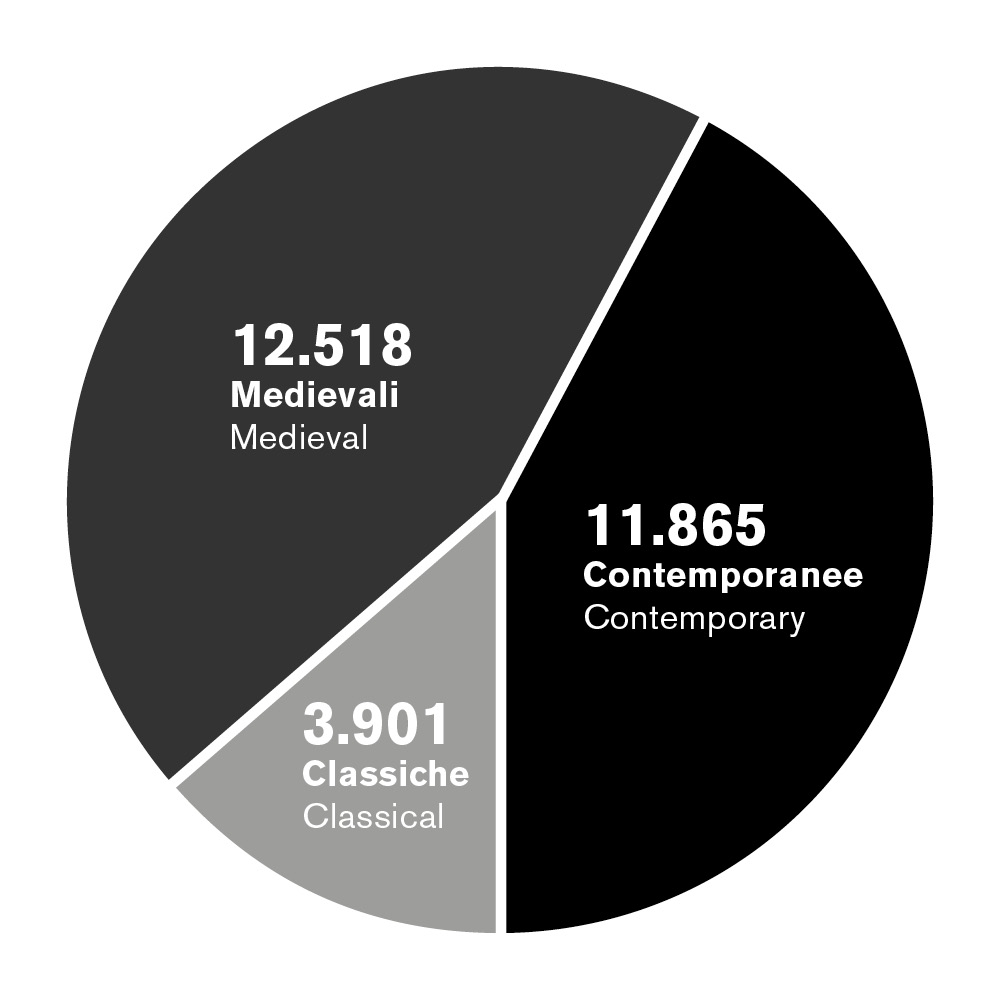

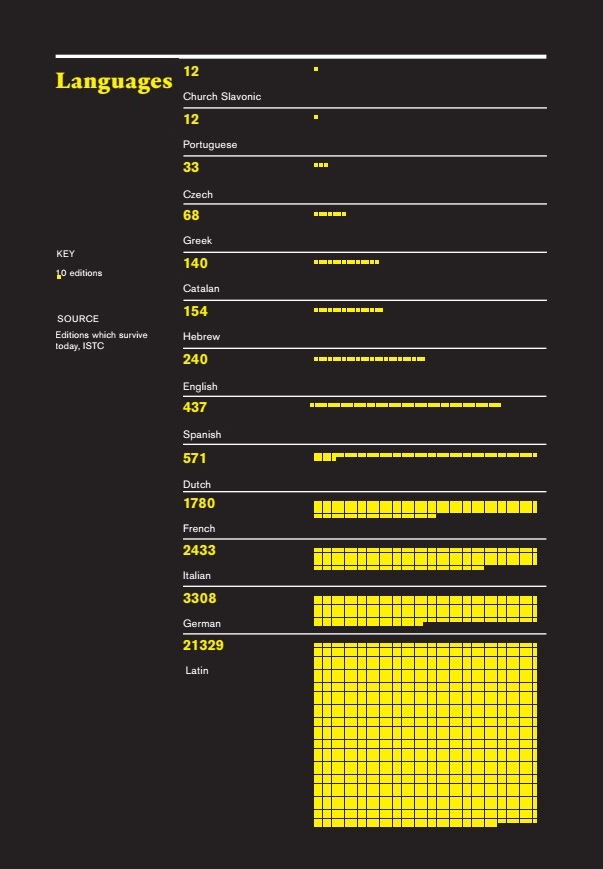

Subjects, periods, languages

Theology was unsurprisingly the most printed subject, but Law came a close second and Grammar texts, despite having been lost in large quantities, still came fourth, a clear reminder of the connexion between printing and the growth of literacy

Subjects, periods, languages

Many more contemporary works were put in print than previously thought

Subjects, periods, languages

Latin was the language of communication across Europe

From Decoration to Illustration

Illustration

From hand decoration to printed illustration

Images and decoration applied by hand were common in manuscripts, therefore solutions were immediately sought to insert them in printed books. Printed copies were finished with hand decoration. In the 1470s some printers used decorative wooden blocks to impress, on individual copies, decorations which were often coloured in by hand. From the 1480s onwards, illustrations – woodcuts or metalcuts – were set with the text, to save time. Then they might be coloured in by hand.

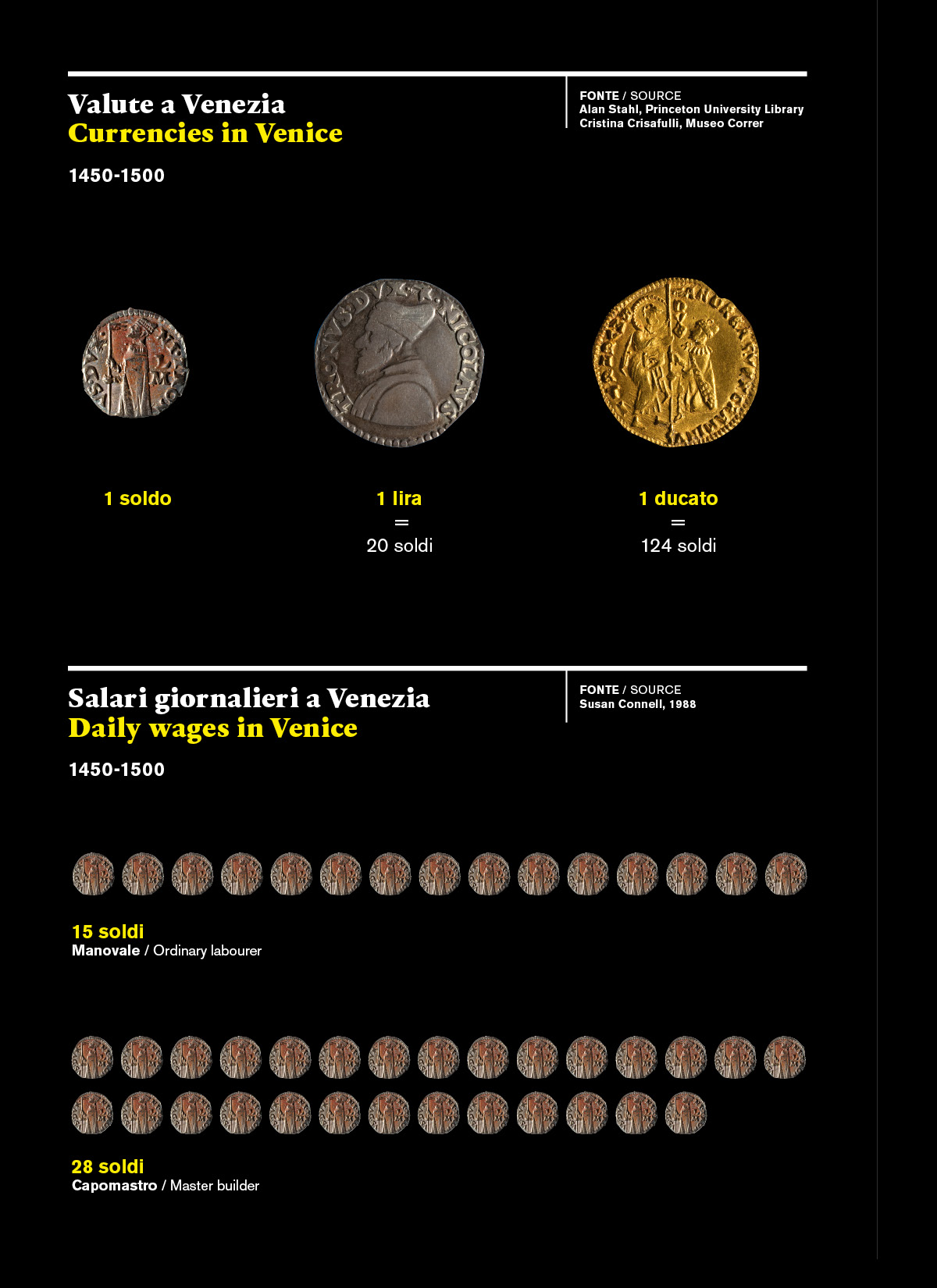

The Cost of Books and the Cost of Living

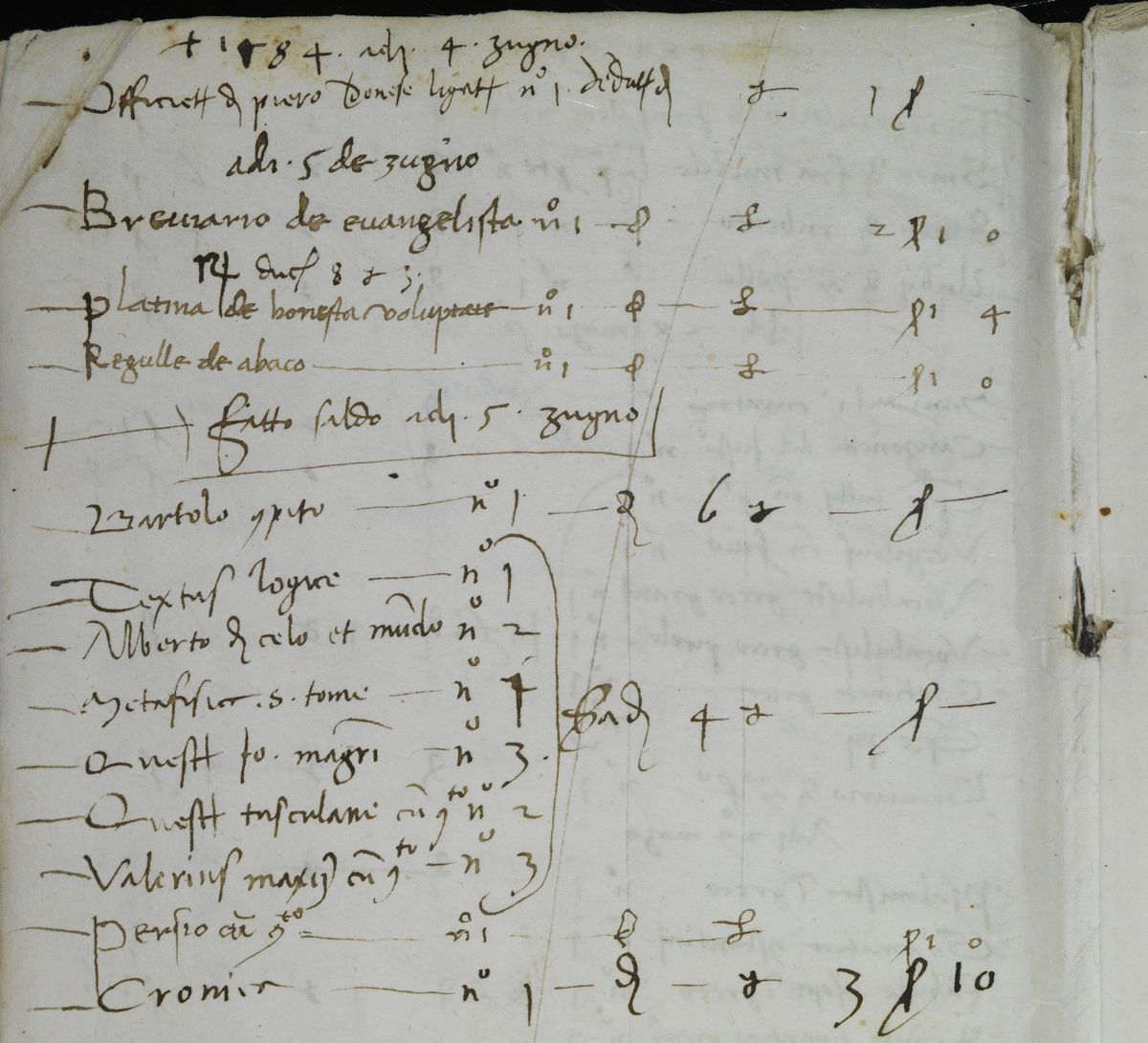

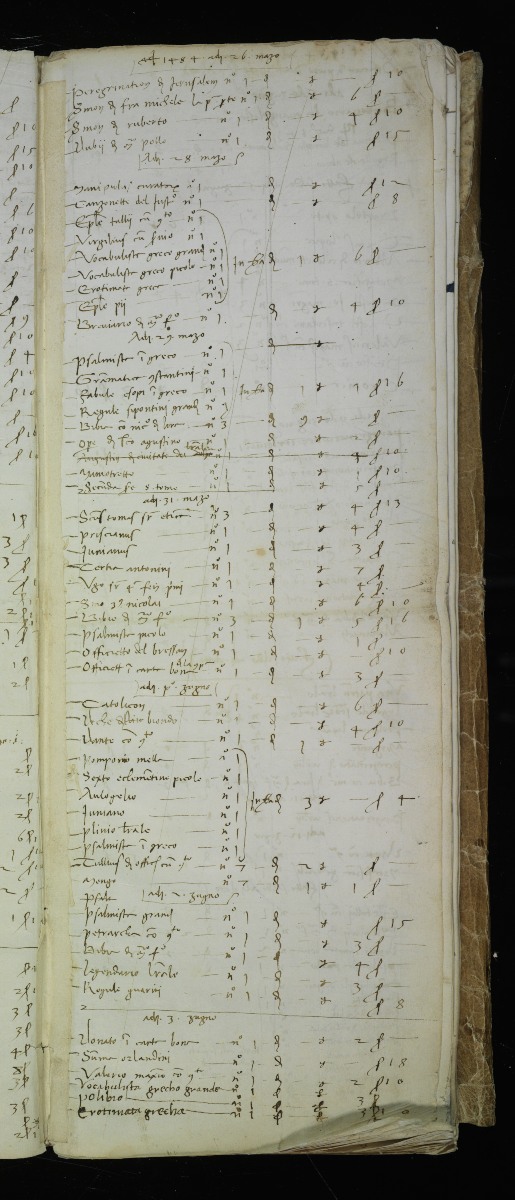

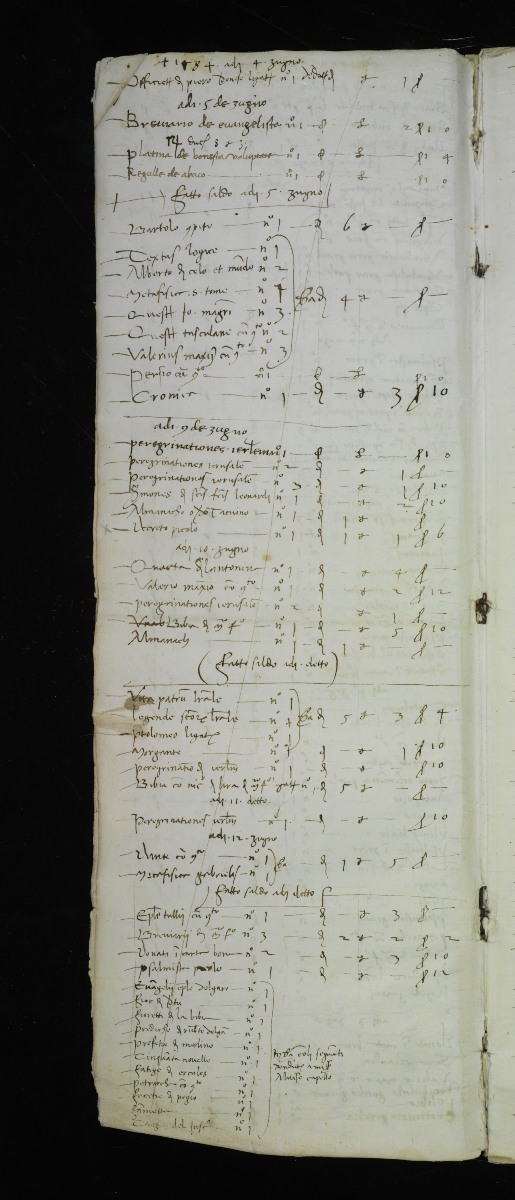

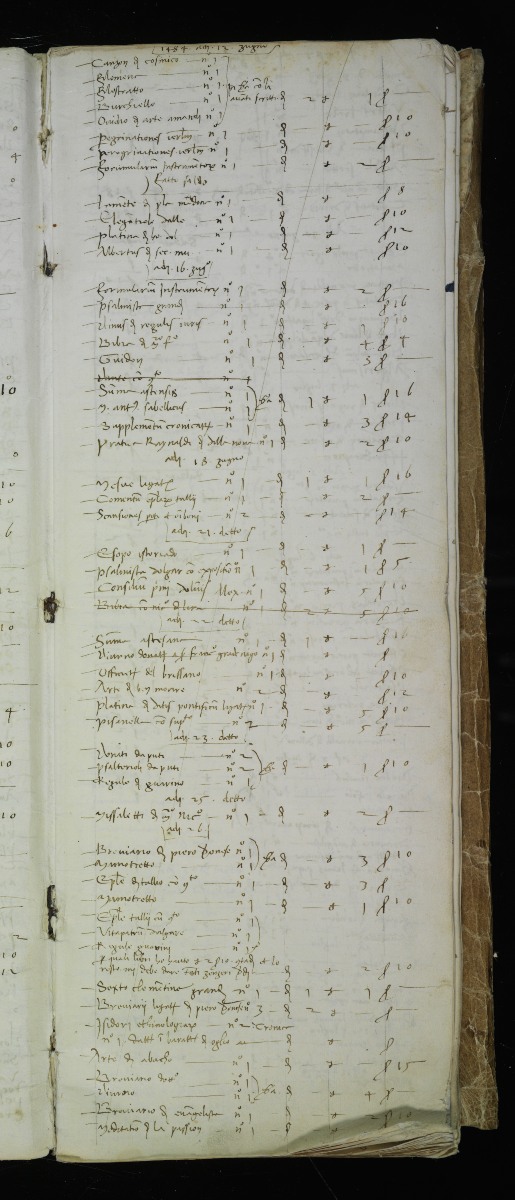

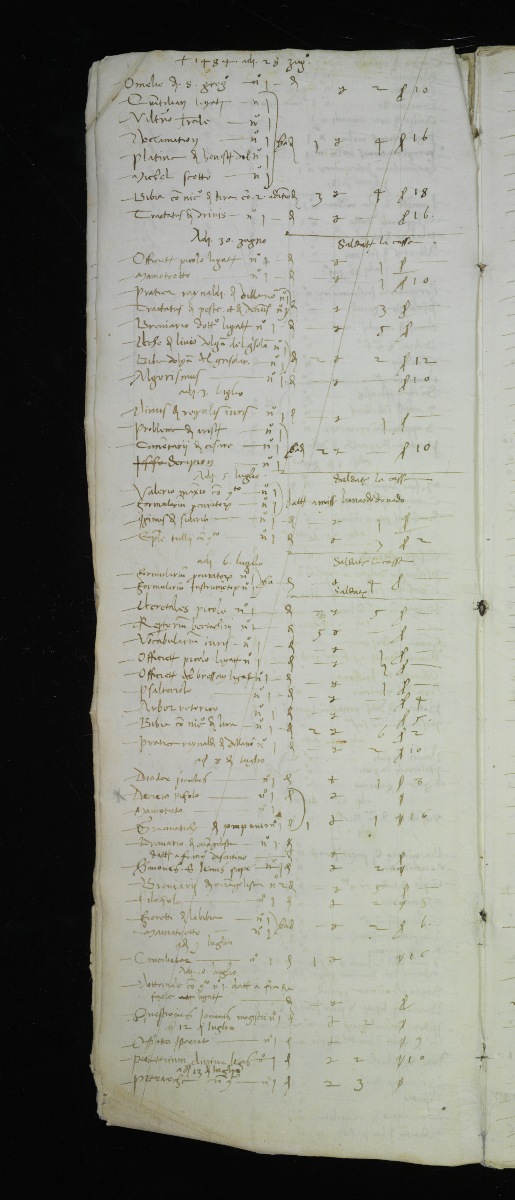

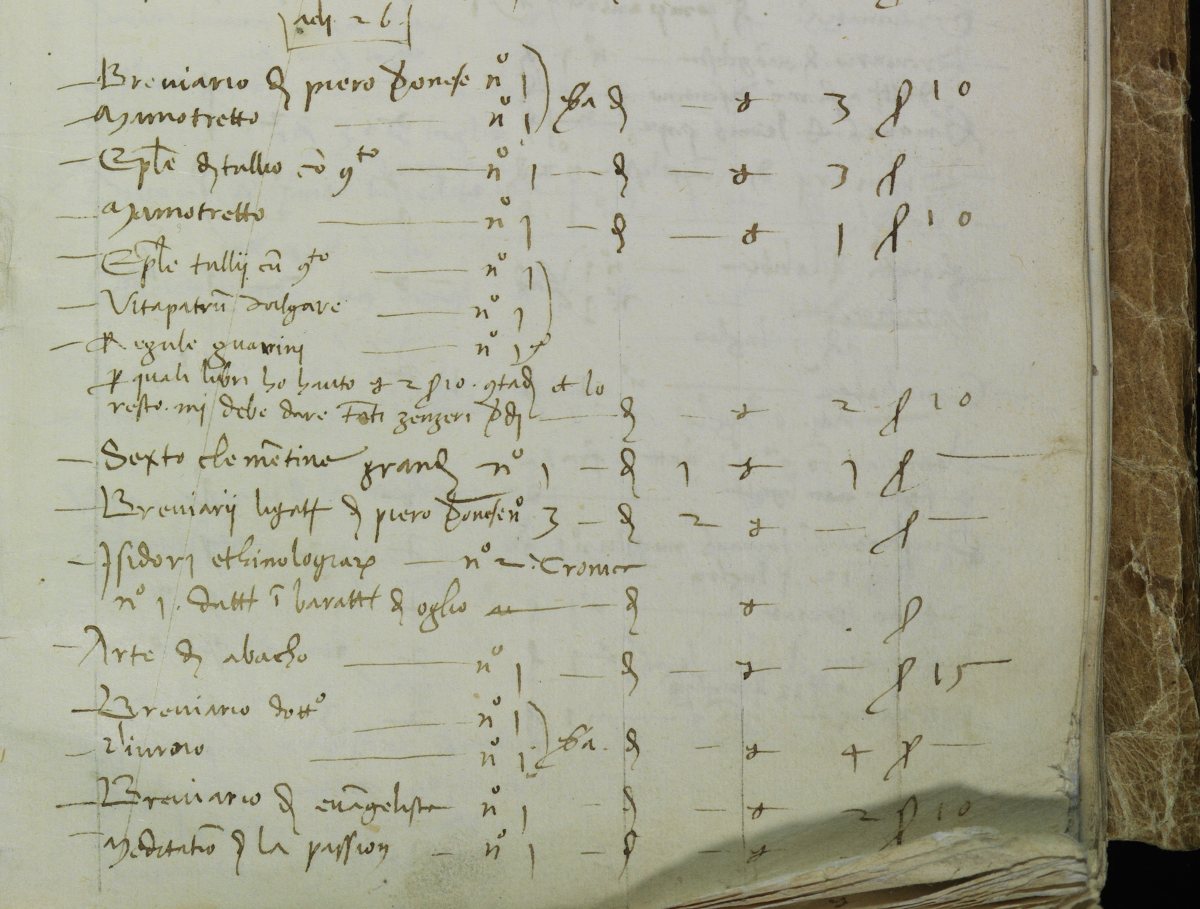

Cost of books and cost of living in 15th-century Venice; account book of Venetian bookseller Francesco de Madiis; zornale

The Zornale of the Venetian bookseller Francesco de Madiis is the financial account of the printed books he sold during the period 1484-88. This extraordinary document lists the sale of 13,000 printed books with their price, just 15 years after printing was introduced into the city. We now know the price of any kind of book and can compare it with the cost of living. In late 15th-century Venice, people used soldi, lire, ducats. 20 soldi made 1 lire, 6 lire and 4 soldi (or 124 soldi) made 1 ducat. We cannot compare today’s prices with those back then, but we can try to understand them.

Best-sellers worst-survivers

Printing and literacy in the 15th century

After 500 years since the invention of printing, we have lost a great many books, especially ordinary and very popular books, the first worn out, the second reprinted over and over, their early editions thrown away. Have you kept a copy of your first school book? Or an old tourist guide? So, how can we understand which were the best sellers of the 15th century?

- We look at the 8,000 editions which survive today in just one copy in the world (many examples on show)

- We study the account book of a Venetian bookseller at the time: a unique insight into what was on sale at what prices

What survives today does not match what was popular then. What will survive of today’s digital production?

The Bible was not the most printed nor used book. Books for primary education were printed and sold in large quantities: the most tangible sign of the link between the spread of printing and the growth of literacy. Destroyed in vast quantities, these books mostly survive today in just one copy, re-used as binding material. Alongside Gutenberg’s Bible, the early Mainz presses printed numerous editions of the grammar by Donatus. Widely disseminated these schoolbooks survive only in fragments.

The Church and the Press

The Bible in Translation

15th-century printed Bibles in the vernacular languages

From its beginning, members of the Church were very actively involved with the new medium. They acted as benefactors and sponsors (Cardinals Nicholas of Cusa and Bessarion, Pope Sixtus IV), as editors and correctors (Franciscan and Augustinian editors of liturgical texts, mathematics, logic, and literature), as authors of lay as well as religious works (Werner Rolewinck), as translators (Nicolò Malerbi of the Camaldoli order in Venice translated the Bible into Italian), as printers (Benedictines in Augsburg, Erfurt, Subiaco near Rome; Augustinian Hermits in Nuremberg; Cistercians in Zinna; the Dominican nuns of Ripoli at Florence; Fratres Vitae Communis in Marienthal, Rostock, Brussels, and Cologne; Franciscans of Santa Maria Gloriosa in Venice), and finally, as book users and owners, both privately (Jacobus Zenus, Bishop of Padua, Cardinal Grimani in Venice, and the thousands others now identified in MEI database) and institutionally (thousands in the MEI database). The preservation of thousands of incunables for posterity has to be credited in large part to the libraries of religious institutions.

Bibles in various European languages were published and circulated around Europe already 50 years before the famous German Bible of Martin Luther (1522-34). Who used these thousands of Bibles? Ongoing research at the University of Oxford is examining the surviving copies, beginning with the Italian editions.

Women and the press: female authors, printers and readers

Women and the Press

Female authors, printers, readers in the 15th century

Women wrote, chose, illustrated, and proofread the text, set the type, operated the press, ran the business. Women also commissioned books to be printed for their use, as at San Zaccaria in Venice, and of course they also read books.

Leonardo’s books: in Italian, printed, and ordinary

Leonardo da Vinci’s library

A list made by Leonardo of 38 books in his possession at the end of the 15th century. The works, in print, are the same as those sold by De Madiis in Venice. If Leonardo had the same books that many other people were buying, and book-buyers were not all geniuses (like him), then we can say that Leonardo had an ordinary library.

We do not know the exact editions of the works Leonardo lists, but here are images of some of the editions which were on the market when he acquired his books – actual copies from his library have so far not been traced.

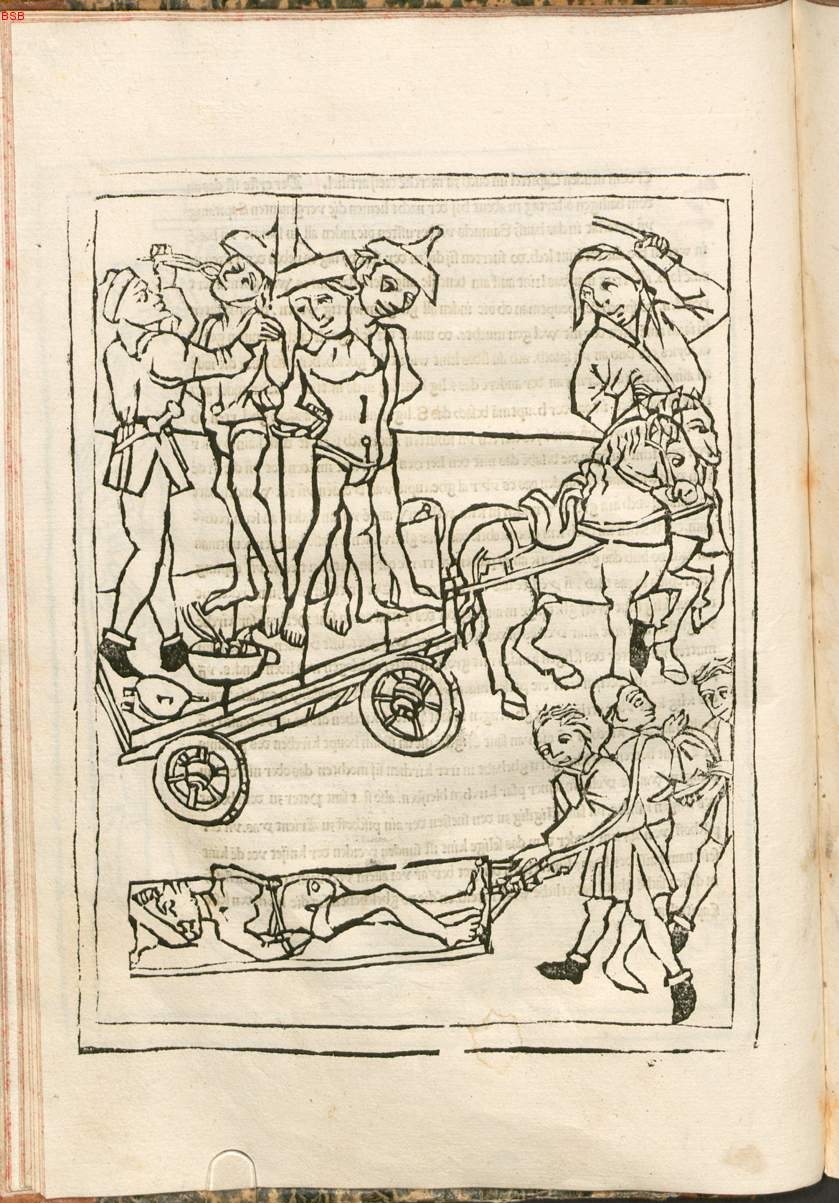

Use and misuse of printing. Antisemitism and the new medium

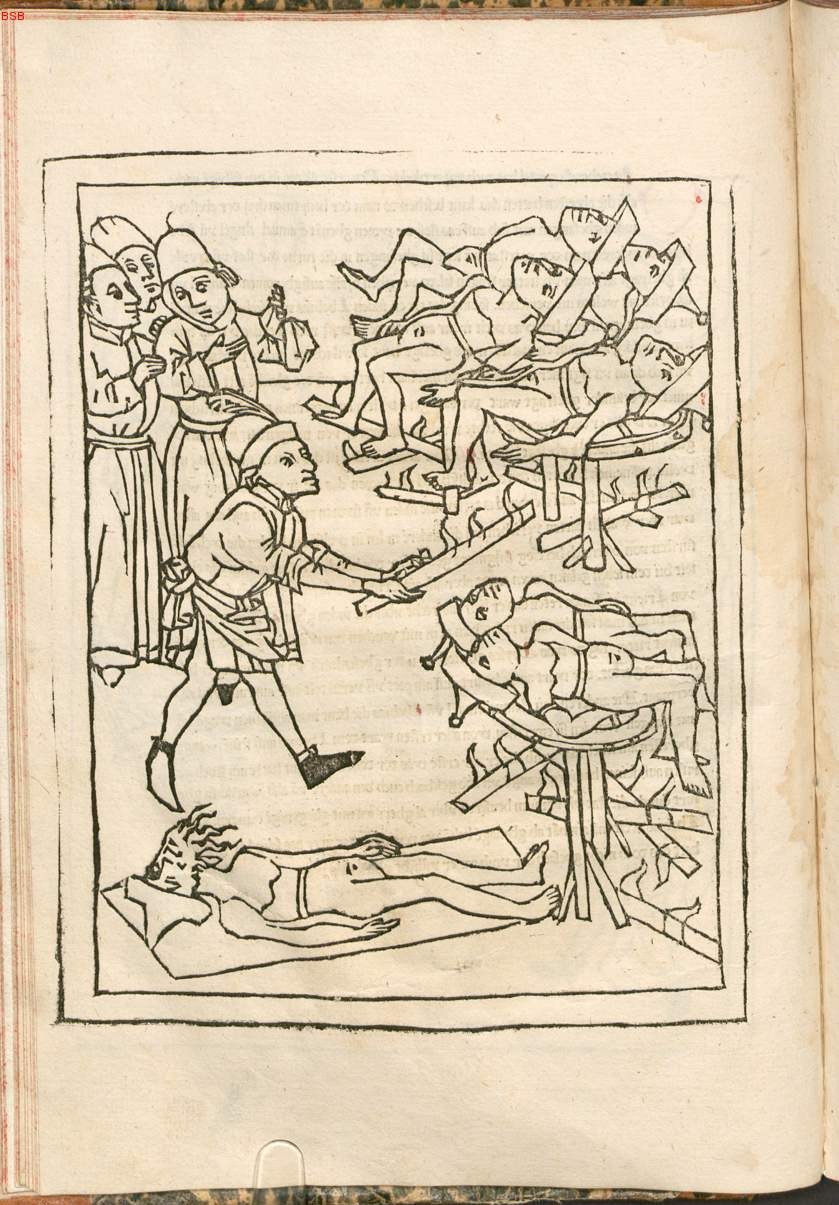

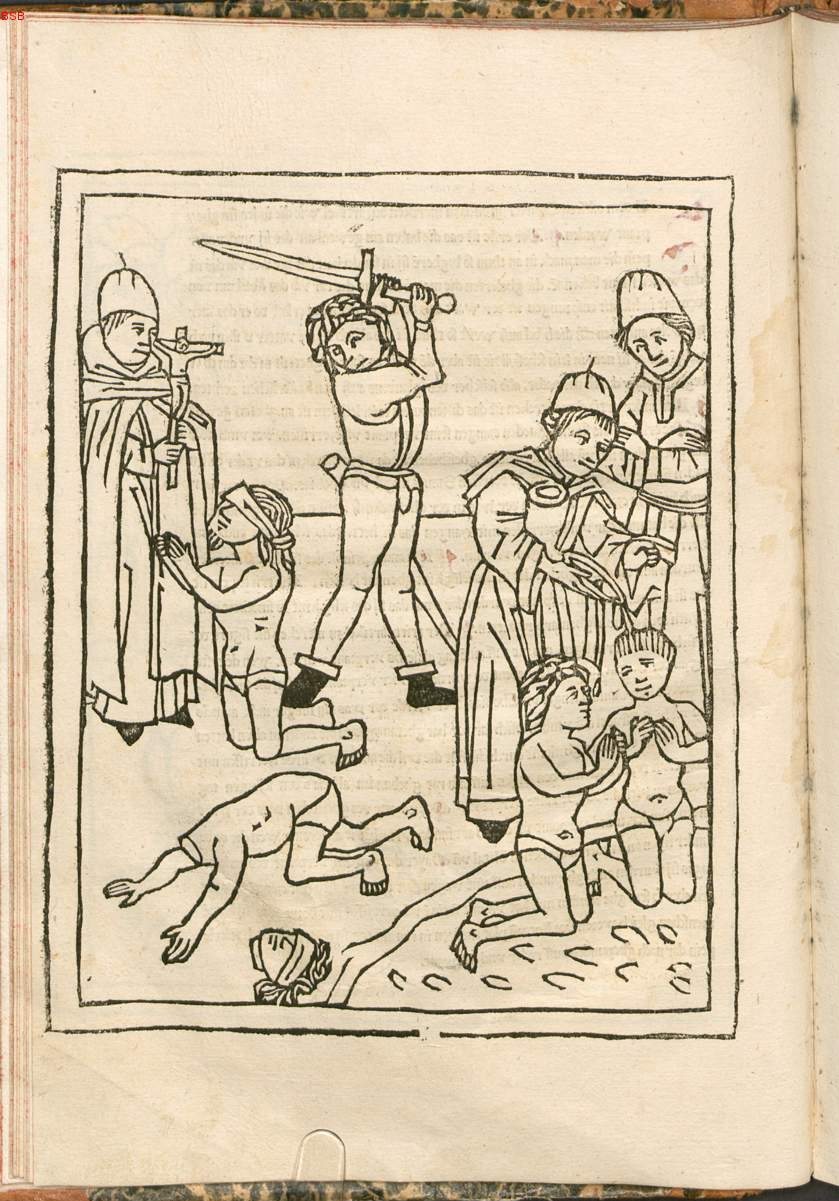

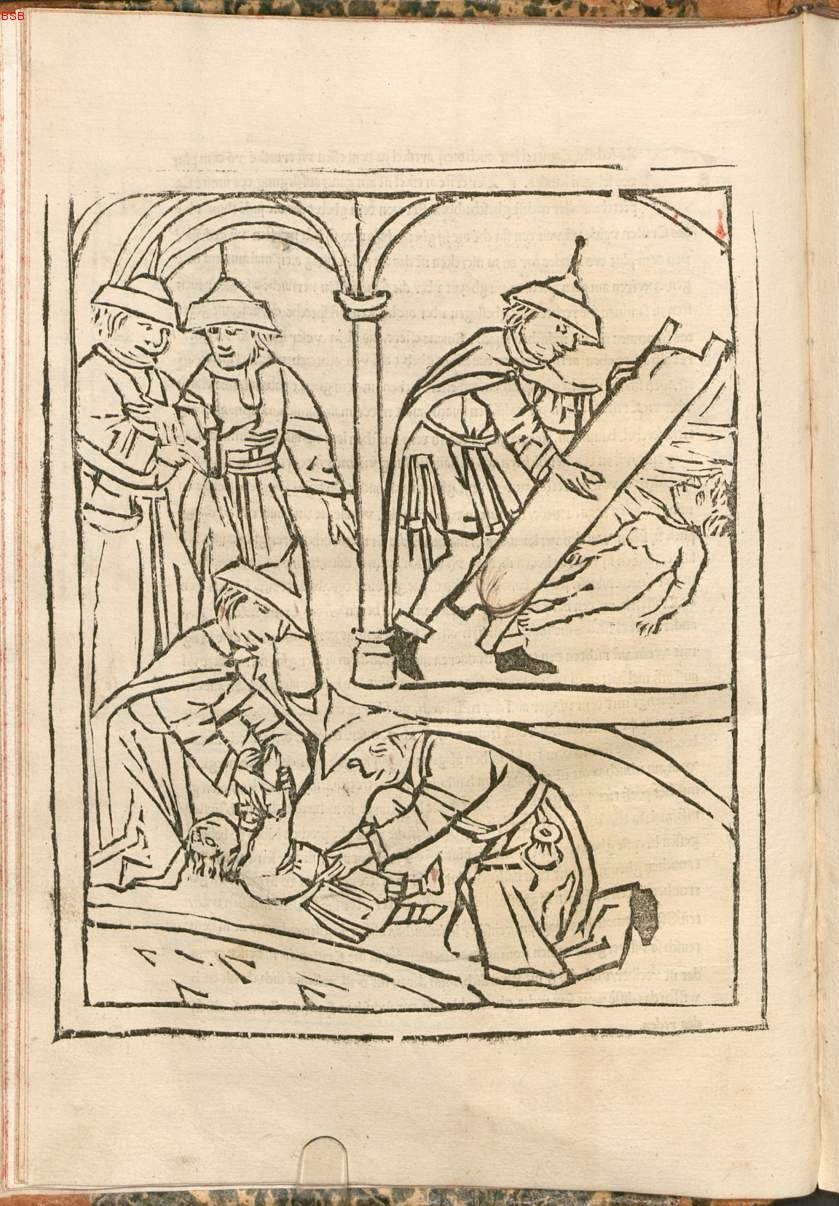

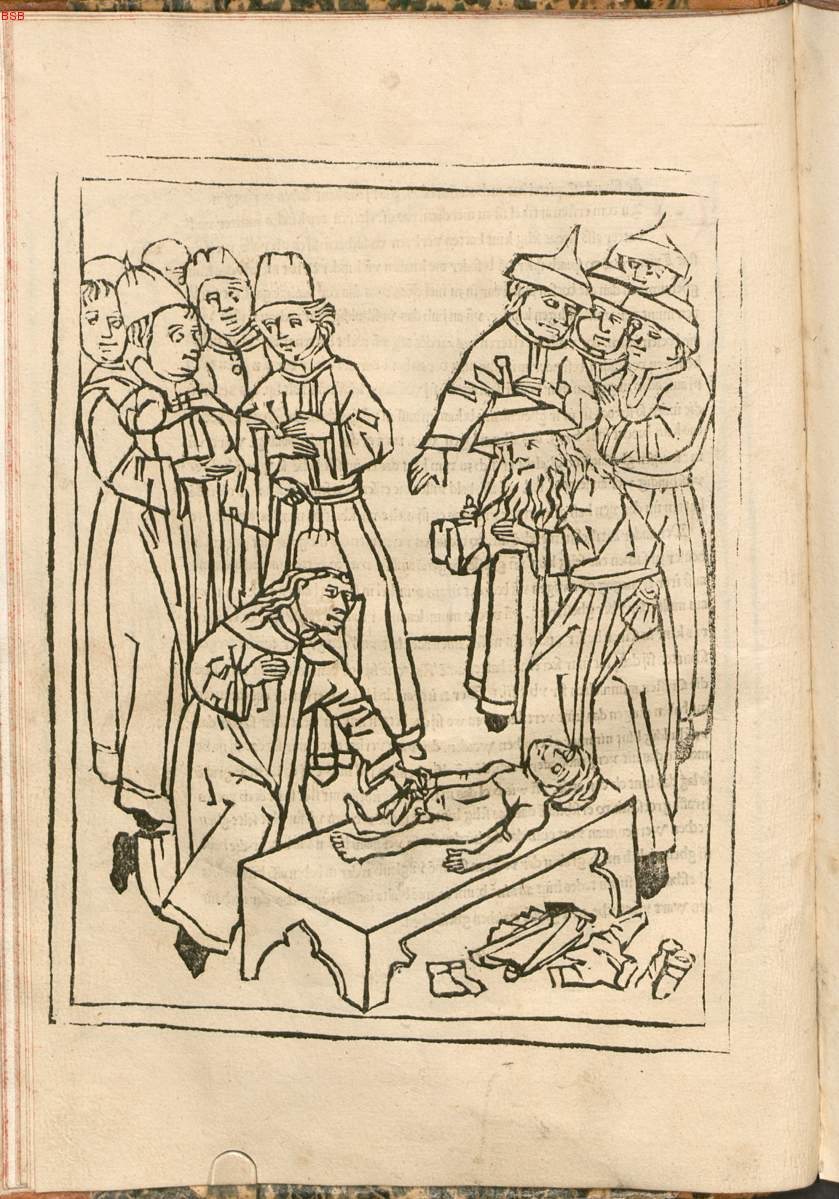

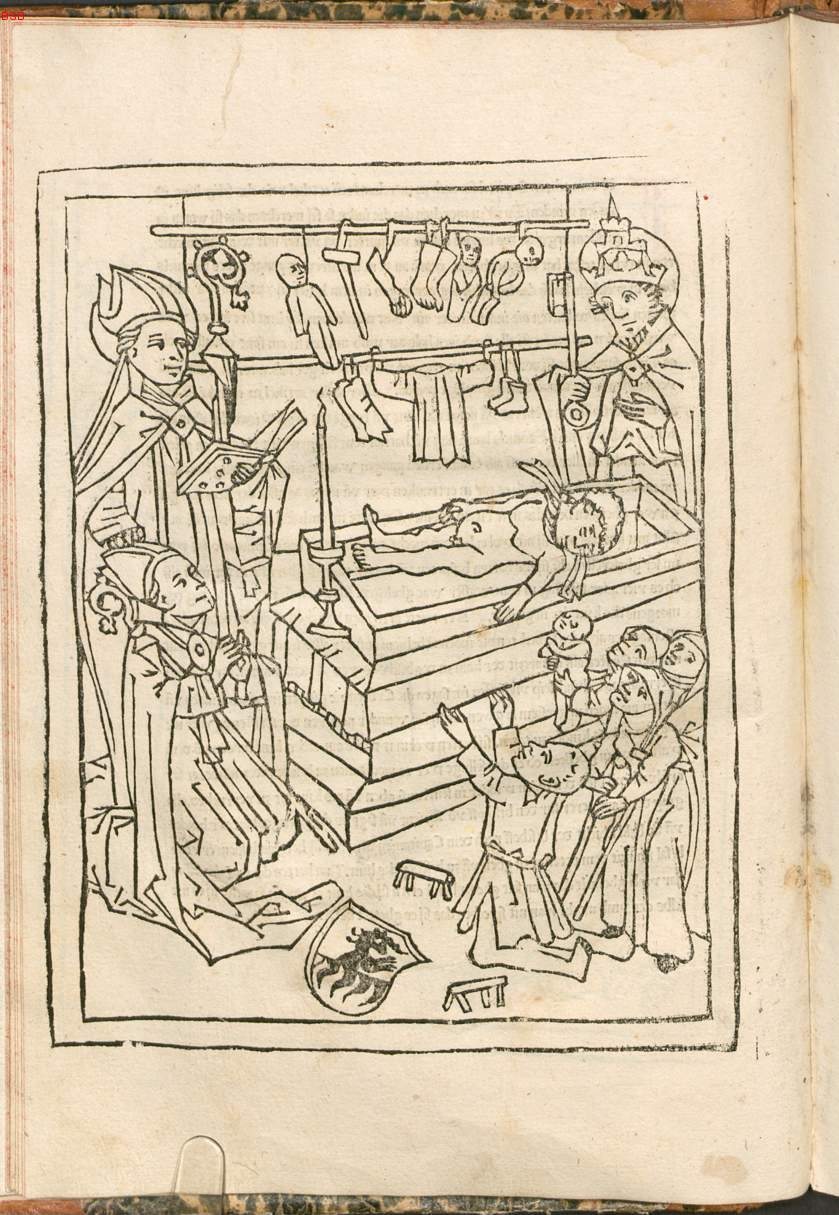

A carefully orchestrated case was mounted against the Jews of Trent, in northern Italy, following the murder of Simoncino, a little boy, in the city in 1475. The bishop-prince Giovanni Hinderbach accused them of ritual murder. Members of the Jewish community were arrested, put on trial, and after confessing under torture, burned. Printed editions of the story, with illustrations, were immediately produced.

Historie von Simon zu Trent, Trent: Albrecht Kunne, 1475 (Munich, BSB)

The forensic examination of the child’s body by the physician Giovanni Mattia Tiberino was published in Trent in 1475, confirming the ritual murder, and it was reprinted in 13 editions published in Rome, Treviso, Mantua, Sant’Orso, Venice, Verona, Naples, Cologne, Augsburg, and Nurenberg. Tiberino also published a complete history of the case, as well as verses, and an epitaph.

Against doubts raised within the Church, the legal opinion of the influential canon lawyer Giovanni Francesco Pavini was also published in Rome in 1478.

At the same time Hinderbach solicited influential writers to publish works in support of the creation of a cult surrounding the little boy: works by Raffaele Zovenzoni, Pomponio Leto, Platina, Felice Feliciano. Verses on the ‘martyrdom’ were written by Giorgio Sommariva and Girolamo Campagnola, Leonardo Montagna, Cimbriaco, Giovanni Calfurnio, Ubertino Posculo.

The campaign was also supported by the anti-Jewish sermons of some Observant Franciscans and Augustinian Hermits, such as Silvestro da Bagnoregio, Proctor General of the Augustinian Hermits.

Opposition and scepticism existed from within the Church, but were overcome by the power of the new medium. Simoncino became the symbol of the city, and so was included to represent it, in Schedel’s famous History of the World of 1493.

The cult was made official in 1588 and Simoncino beatified. It was only in 1965 that the cult was abolished, when an official paper of the Catholic Church – Nostra aetate – finally sanctioned the revocation of the deicide accusation against the Jews, and any form of antisemitism was forbidden.

Was this the first case of fake news in print?

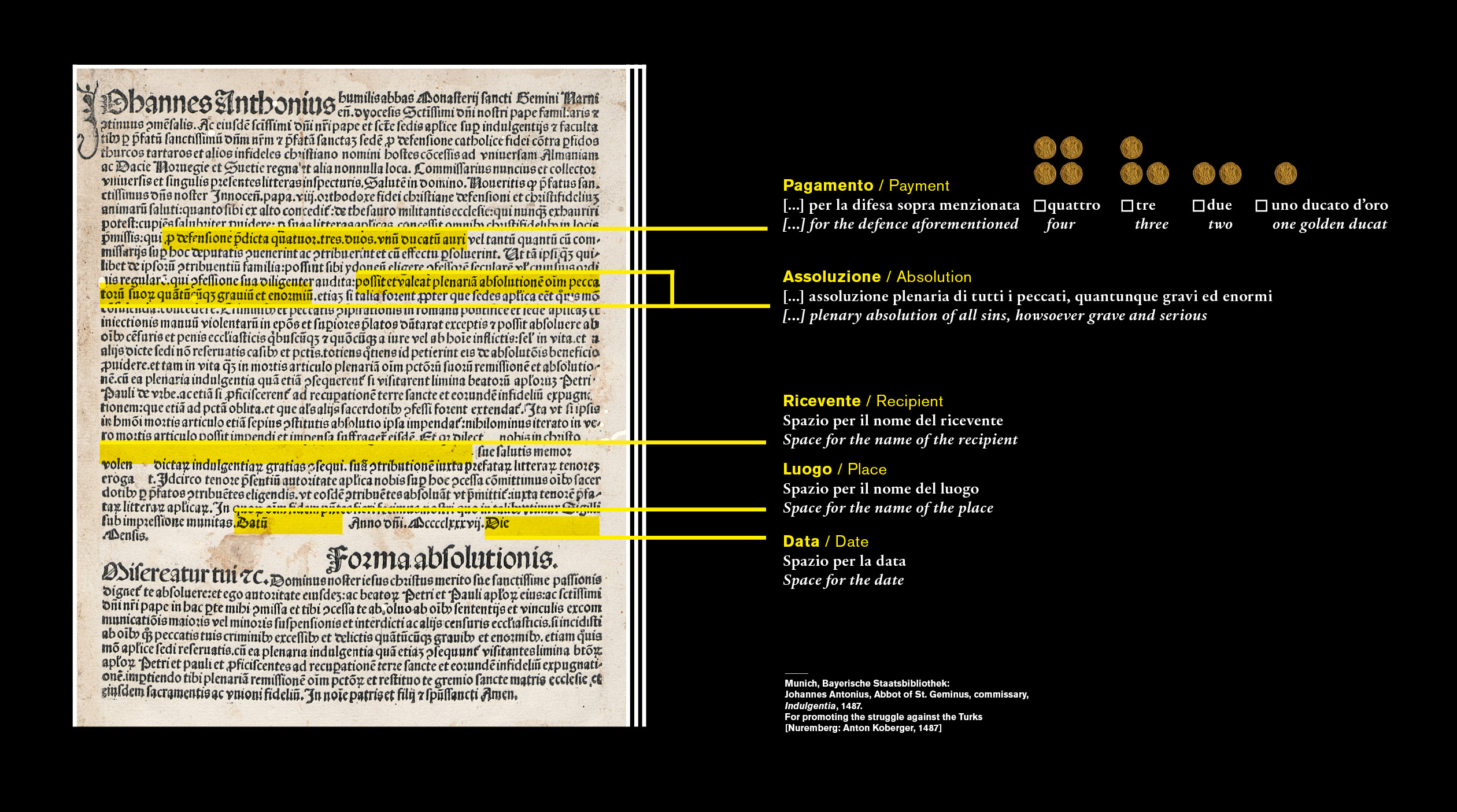

Use and misuse of printing. Religious ‘crowdfunding’: indulgences

Hundreds of indulgences, in thousands of copies, were printed to raise money for the Catholic Church, and customised by hand, like forms with blanks which needed to be filled in by hand. Any sin would be forgiven in exchange for donations. As proof of forgiveness the seller provided a certificate, the indulgence. Many indulgences were sold to repair churches or fund hospitals, but also to finance the war against the Turks who were advancing into Europe. Printing allowed the practice to expand in scope: it is this practice that Luther would attack in the following century.

Surviving copies are very rare because people who bought them tended to be buried with them.